Project Overview

In an initiative that combines cultural research and sustainability, the University of Cabo Verde (Uni-CV) and Kennesaw State University (KSU) in the United States have launched a project to study the dynamics of artisanal alcohol, known locally as grogue, and its impact on Cabo Verdean communities. The project, entitled “Contested Values and Sustainable Livelihoods of Artisanal Alcohol in Cabo Verde“, is funded by the US National Science Foundation’s Division of Behavioral and Cognitive Sciences Cultural Anthropology program (award #2243434) and has a budget of USD 313,827.00 to be implemented over three years (7.15.23-6.30.26).

Led by KSU economic anthropologist Brandon D. Lundy, the research team is made up of an interdisciplinary group that includes Nancy Pullen and Mark Patterson, both geographers and geospatial scientists, and Monica Swahn, an alcohol epidemiologist and Dean of the Wellstar College of Health and Human Services at KSU. On the Uni-CV side, the project includes Maria de Lourdes Silva Gonçalves, an expert in anthropology and rural development, and Elisângelo Monteiro, a chemical engineer and manager and owner of ETAConsulting.

The study focuses on understanding how grogue, an integral part of Cabo Verde’s cultural heritage, is perceived and managed by local communities, both in urban and rural contexts. The research seeks to uncover how this alcoholic tradition can simultaneously reinforce and challenge local livelihoods under constrained economic conditions.

To achieve these goals, the researchers adopt a collaborative ethnographic approach, using interviews, surveys, consumer diaries, and socioeconomic networks to generate StoryMaps and open-access publications that illustrate the complexity of grogue production and its role in Cabo Verdean society.

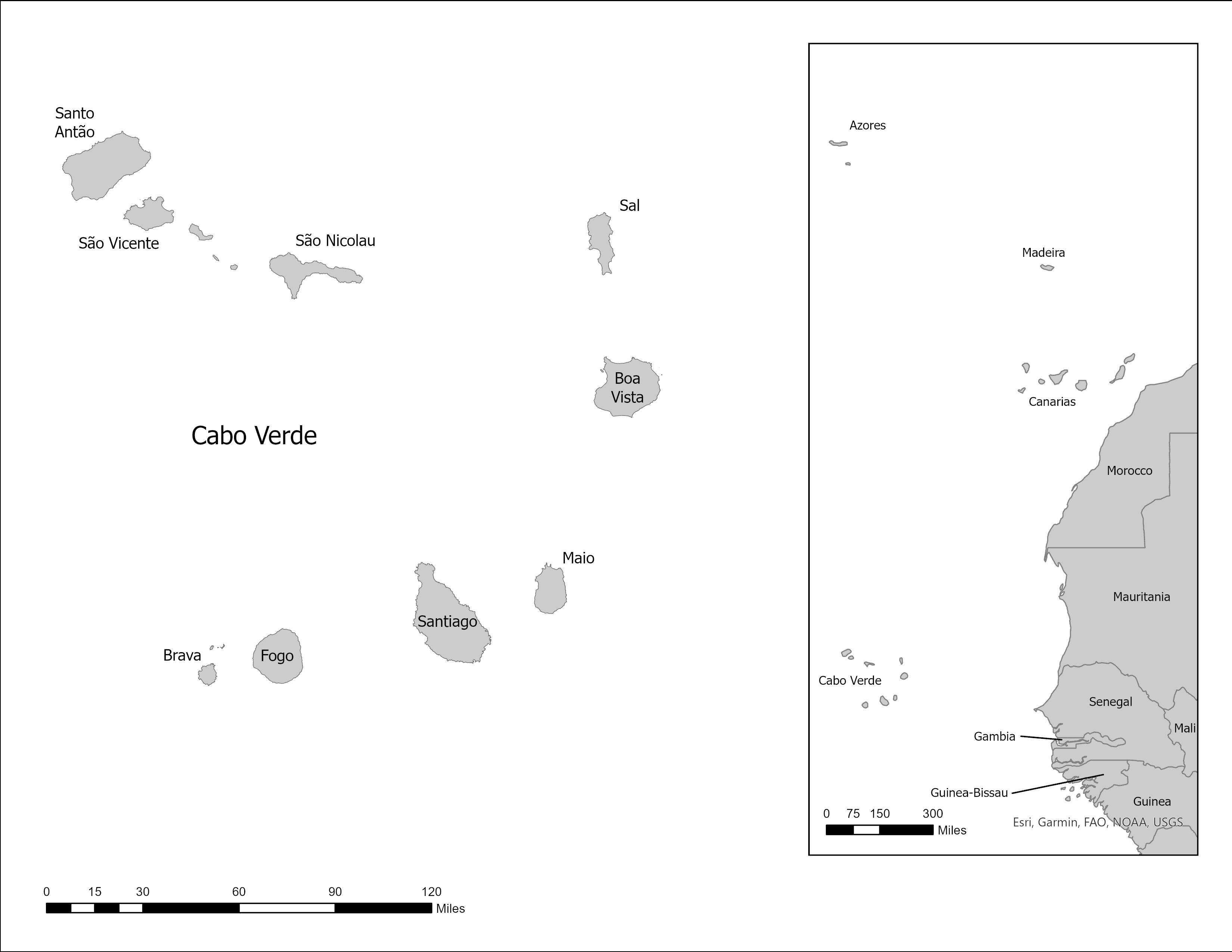

To date, the team has carried out extensive fieldwork on the islands of Santiago and Santo Antão, where grogue is a cultural and economic presence. The involvement of Uni-CV students, such as Helder Tavares and Berenice Tavares, has been crucial in mapping grogue production units, but also in conducting interviews and administering questionnaires.

Story of Grogue

In the fifteenth century, Europeans colonized a series of Atlantic islands, moving like stepping stones from Madeira in 1415 to Cabo Verde by 1456. Due to its strategic location close to the African mainland, Cabo Verde quickly became the center of Portuguese activity in the Atlantic, building its economy on enslaved peoples, strategic ship trade, and an untenable agricultural system. A creole society, some mix of African and non-African ethnicities that formed a unique cultural heritage, emerged from transatlantic trade and settlement. Adopting the agricultural experiment circulating the Atlantic, sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) was imported from Madeira and planted in Cabo Verde by 1490 on the largest islands of Santiago and Santo Antão with the most arable land and water. An ancient domesticate making its way through Europe, sugarcane is believed to have originated in Papua New Guinea.

At the time, sugar was a luxury good that only the rich could afford. Because of the climate and persistent lack of rain, without extensive irrigation, the bulk of sugarcane production in Cabo Verde would not have been possible. This suggests a tremendous outlay of infrastructural investment even given the limited returns. Why were communities in Cabo Verde willing to invest so heavily in this largely failed agricultural experiment? The answer may lie partially in its potential to produce a strong spirit known locally as cana or grogue. Cabo Verdean grogue (also known as grogu or grog, derived from English)—much like Brazilian cachaça, Caribbean rum, and South American aguardiente (Portuguese: aguardente)—is a sugarcane-based distilled spirit found throughout the burgeoning Atlantic world, particularly where sugarcane was cultivated and traded. It may be that distillation in Cabo Verde began in Engenho (which is also the Portuguese word for a sugarcane production facility still used throughout Brazil), a neighborhood near the earliest port of Santiago, or in Ribeiro Grande, the first European settlement in Africa, today known as Cidade Velha and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Although difficult to corroborate, there may even be a mention in Christopher Columbus’s lost 1508 journal of inhabitants of Santiago making sugarcane-based spirits using a trapiche made from Sicilian wood that would have started as the mast of a ship, and an alambique, the new Arabic distillation technology also making its way through Europe and into the Atlantic around the same time as sugarcane.

Historically, there was little government protection for the local sugar and alcohol economy of Cabo Verde since it was part of the larger Atlantic colonial enterprise. For example, brandies and wines from Europe glutted the Cabo Verdean markets between 1849 and 1852 as import restrictions were eased. By 1881, the export of Cabo Verdean sugar had been banned by the colonial regime entirely. Local farmers likely turned to distilling fermented sugarcane juice to make aguardente, which they named grogue after the British royal navy’s watered down alcohol rations. The central Portuguese government in Lisbon, after getting wind of this expanding enterprise on the islands, criminalized the importation of distilling equipment. By 1941, the Portuguese colonial rulers outlawed the production of sugarcane spirits altogether, although this was short lived due to increasing global demand after World War II. By 1945, the Portuguese halved the duty and lifted the production ban with complete abolishment of the decree by 1968. When the new Movement for Democracy (MPD) came to power in 1991, Cabo Verde’s government embarked on a process of market-oriented economic reforms. One such reform was the liberalization of grogue production to promote and expand agriculture. This decision allowed for cheap refined sugar imports leading to the “Grogue of Democracy” in which the glut of sugar impaired the quality and value of grogue as it became ameliorated with refined sugar.

After this crisis affecting the grogue economy, a guild of grogue producers was established in Santo Antão in 2008 to honor, value, and promote grogue as an important cultural resource that needs to be protected known as CONGROG (Confrérie du Grogue de Santo Antão).

Decree-Law no. 11 enacted on February 12, 2015, established new rules governing the production of sugarcane spirits. This decree defined grogue as a “sugarcane spirit produced in Cabo Verde … obtained from the distillation of naturally fermented must from sugarcane, which contains peculiar sensory characteristics.” This was followed by Resolution no. 87/2018 to establish compliance and implementation guidance for Decree-Law no. 11/2015.

See: Gilabert, Philippe. 2023. Grogue: From Sugar Cane to Glass. Mindelo, Cabo Verde: Edition Belavista.