Explore the Cultural Impacts of Grogue on Cabo Verdean Culture

Since 2015, the production of grogue has faced scrutiny, with several government legislations imposing restrictions on both production and consumption. These regulatory efforts focused on enhancing the quality and consistency considering national and international food standards, environmental protection, public health, and consumer and producer rights. However, these impositions have unintentionally targeted small scale producers. To this day, the people of Cabo Verde fight to preserve the spirit that represents the connection of people and place, serving as a symbol of their identity.

Ferro Gaita- Bejo Batafada

This popular song from the premiere funaná band Ferro Gaita recounts how rural youth are pulled from their traditional roles in the countryside including grogue production as they heed the call of the larger world.

A Ilha Fantástica

A novel that vividly portrays the sentiment of struggle and coping under the Portuguese colonial yoke.

“And after lowering him into the grave, and while the women raised the final traditional farewell, the men, solemnly, remorsefully, tears in their eyes, uncorked a bottle of grog and poured it over Uncle Maninho’s body, this act being the final homage to the one who was on his way to the land of nostalgia.”(1994, Ilhéu Editora, p. 43; Germano Almeida & Russell Hamilton, 2010, Transition 103: 42, 43)

[E depois de o meterem na cova e enquanto as mulheres levantavam a guisa final de despedida, os homens, solenemente, compungidamente, as lágrimas em todos os olhos, abriram uma garrafa de grogue e despejaram-no sobre o corpo de Ti Maninho, uma última homenagem àquele que ia para a terra da saudade.]

Note

To many, grogue symbolizes Cabo Verdeanness: its land, people, ethos, and essence. To drink it is to imbibe the terroir of the islands.

Zeca -pa ‘ Grogu ‘

This funaná and accompanying video celebrate and showcase the joys of traditional grogue production in Cabo Verde and its importance in the community.

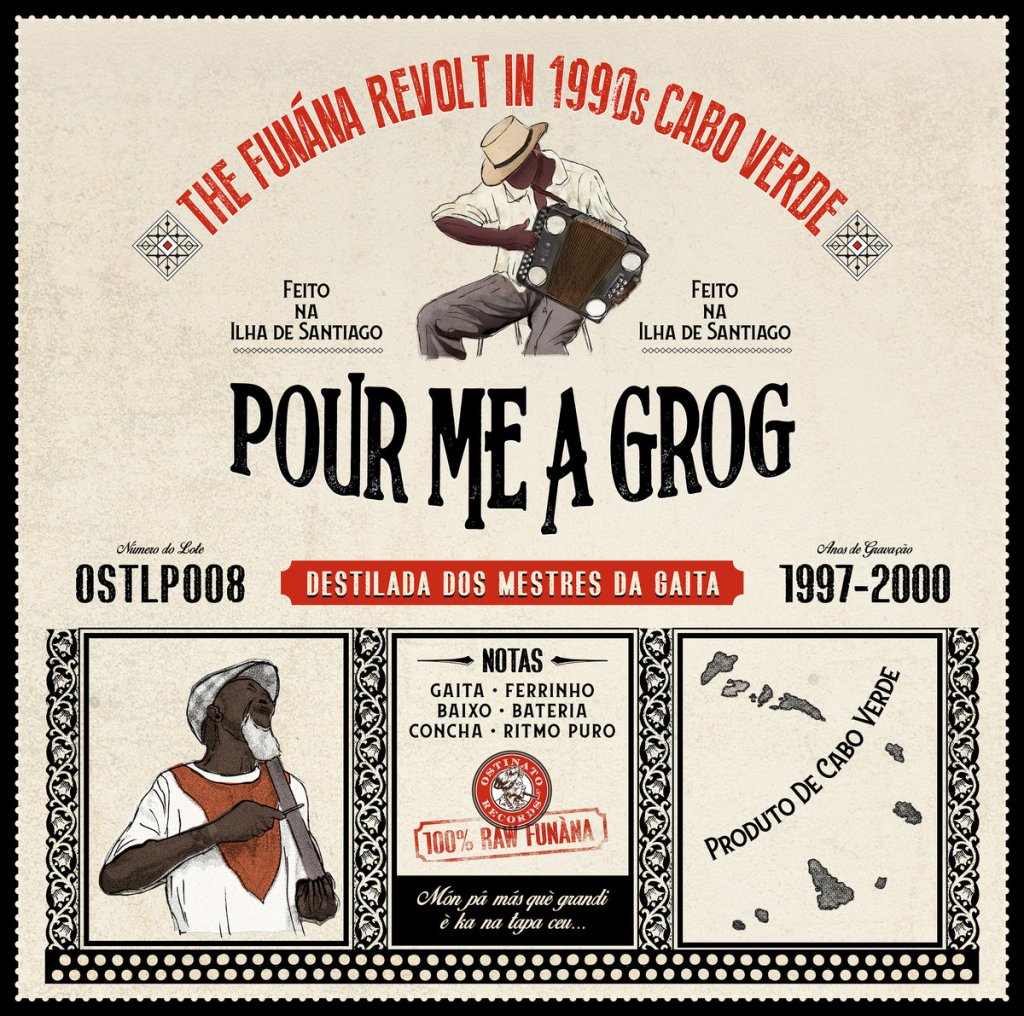

Pour Me a Grog: The Funaná Revolt in 1990s Cabo Verde

“Pour Me a Grog: The Funaná Revolt in 1990s Cabo Verde,” released on October 14, 2019, is a celebration of Cabo Verdean pioneers and their rebellious culture. Featuring various artists, the album encourages listeners to embrace freedom through dance and the enjoyment of grogue. It serves as a tribute to the spirit of defiance and resilience embodied in Cabo Verdean music

MIRRI LOBO – Encomenda de terra

Cabo Verdean locals are expected to send “things from the homeland:” (encomenda de terra) goat cheese, grogue, punch/pontxi (i.e., grogue and sugarcane mixed drink), cookies, canned tuna, and traditional sweets to their friends and family on other islands and in the diaspora. Those who migrate expect to receive products which remind them of Cabo Verde and their family members who stayed behind. Encomendas reduce the longing caused by the distance (i.e., sodade), being received as a token of love and encouraging reciprocity between sender and recipient.

“Menos Álcool, Mais Vida”

Despite grogue’s deep-rooted significance in Cabo Verdean culture, the “Menos Álcool, Mais Vida” (Less Alcohol, More Life) campaign highlights a growing concern in communities. This public health initiative aims to curb excessive grogue consumption, recognizing the potential downsides of this traditional spirit. While the campaign acknowledges grogue’s cultural importance, it strives to strike a balance, promoting responsible drinking habits to ensure a healthy and vibrant Cabo Verde for future generations. Read more about the WHO’s contributions to the campaign here.

Official Regulations for Grogue Production and Consumption:

GrogueBoyz (Dynamo x William Araujo x Elji Beatzkilla) – Grogue

This rap song highlights the public health crisis as a result of grogue consumption as a drug in Cabo Verde, when abused the drink can have negative impacts throughout society.

Chiquinho

Chiquinho is a novel that traces the journey of a young Cabo Verdean boy from his village childhood to adulthood, grappling with education, cultural identity, and the harsh realities of his homeland.

“When the law that emancipated the black people was proclaimed in São Nicolau, there was a great celebration among the enslaved. Jerico, Nhô Miguel Lopes’s one black slave, went to his master’s house when he found out he was free:

‘Master, I have my freedom now.’

‘What do you want freedom for, Jireco?’

‘So that I can go drink palm wine in my country, Nhônhô.’

That same day he got so drunk that he wanted to exchange his freedom for a bottle of grogue. He built a shack in Caleijão and later died there in misery. Some of the freed slaves prospered with the remittances sent by their children who had emigrated to America. The old man Nhenhano Bandeira, who today owns a small store and sugar mill, used to be a slave of Nhô Antóntio Sabina.” (Baltazar Lopes, 2019, Tagus Press, p. 19; translated by Isabel P. B. Fêo Rodrigues and Carlos A. Almeida with Anna M. Klobucka)

Nha manazinha – Nha boi

This female group dressed in traditional batuk garb is singing about the bull (boi) which was used to press the sugarcane with a trapiche, or sugarcane press, during grogue production. Many traditional “boi” songs can be found throughout the Cabo Verdean countryside sung by the boys and men leading the bulls to get them to continue walking in a circle in a repetitive fashion to crush the sugarcane. Most donkey and bull drawn trapiche have now been replaced by mechanized presses.

Grogue is an integral part of not just Cabo Verdean Culture but also their tourism industry. Check out these commercials promoting tourism through grogue.

Nacia Gomi – Rapazinho

This song is a traditional batuk. The singer tells the story of a “little boy” as he grows up in the village. These songs were often used to transmit lessons to the youth about proper behavior and called out those who strayed from traditional norms and broke societies rules.